Ausgabe 1, Band 14 – März 2025

In memoriam Jerome Kohn

Wir trauern um Jerome

Kohn, der am 8. November in New York im Alter von 93 Jahren gestorben

ist.

Er war der letzte Assistent von

Hannah Arendt, ihr großzügiger Nachlassverwalter und der

Herausgeber ihrer Essays („The Promise of Politics“,

„Responsibility and Judgment“, "The Jewish

Writings“, mit Ron Feldman, „Essays in Understanding“,

Thinking without a Banister“). Von ihm finden wir auch Beiträge

im „Arendt Handbuch“. Er und seine ehemalige

Kommilitonin, die Biographin Arendts Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, trugen

statt Konferenzpapers gemeinsam verfasste Dialoge über

Arendtsche Themen wie Erziehung, Souveränität und Gewalt

vor, eine sehr fruchtbare Form der Auseinandersetzung mit einem

Thema.

Der dritte im Bund ist Alexander

Bazelow, der Blüchers Vorträge bei Arendt transkribierte.

Die drei wurden gelegentlich als Arendts Kinder bezeichnet.

2019

erhielt er den "Hannah Arendt-Preis für politisches Denken"

in Bremen zusammen mit Roger Berkowitz.

Nicht zuletzt war Jerome

Kohn sehr humorvoll. So konnte er gelegentlich Kritik mit einem

wirkungsvollen Augenrollen zum Ausdruck bringen.

Mit ihm geht eine

ganze Welt, die wir nur in der Erinnerung bewahren können. Wir

vermissen ihn sehr.

Wir haben einige Freunde und Bekannte gebeten,

uns an ihren Erinnerungen teilhaben zu lassen. Es handelt sich um

Alexander R. Bazelow, Celso Lafer, Martine Leibovici, Volker März,

Adriano Correia, Helgard Mahrdt und Wout Cornelissen. So ist ein

kleines Mosaik entstanden; ein weiteres finden Sie am Bard-College.

https://medium.com/in-memoriam-jerry-kohn.

Beide ergänzen sich.

Die Redaktion

Alexander R. Bazelow, New Jersey

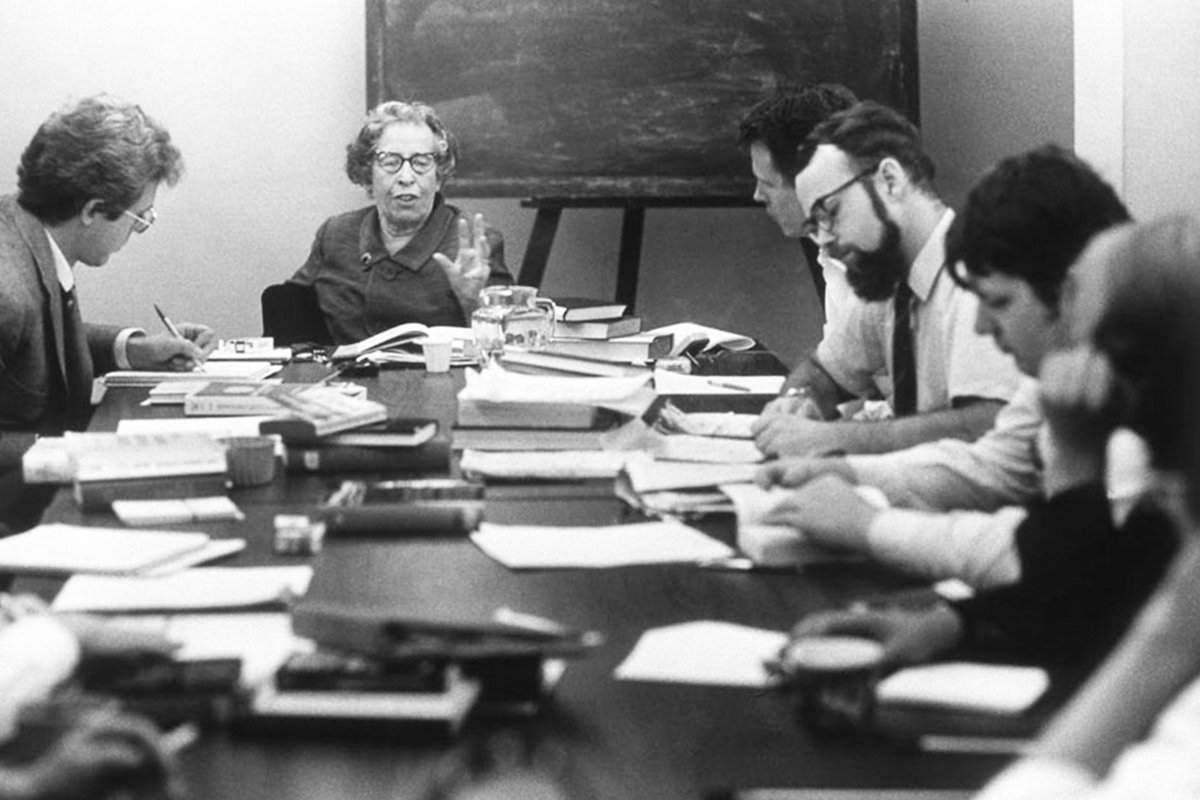

I first

met Jerome Kohn in Hannah Arendt’s classroom at the New School

for  Social

Research during the Fall 1972 Semester. The course was titled

“Selected Writings of Political Philosophers”. Jerry was

her teaching assistant. (left) The syllabus, class list, and Arendt’s

lecture notes can be found in her archives at the Library of

Congress. My first impression was of a very civil person, polite,

soft spoken, and intensely focused on whatever matter was at hand.

There was a sense of decency about him but also caution. He neither

asked for familiarity nor expected it. During the many decades of our

friendship I hardly knew anything of his personal life. It became

apparent, quite early, how much Arendt relied on him. He was

thoroughly familiar with the syllabus and reading material,

understood her trains of thought, and especially how her arguments

connected to her books, lectures and other courses. He was

that rare person of many gifts.

Social

Research during the Fall 1972 Semester. The course was titled

“Selected Writings of Political Philosophers”. Jerry was

her teaching assistant. (left) The syllabus, class list, and Arendt’s

lecture notes can be found in her archives at the Library of

Congress. My first impression was of a very civil person, polite,

soft spoken, and intensely focused on whatever matter was at hand.

There was a sense of decency about him but also caution. He neither

asked for familiarity nor expected it. During the many decades of our

friendship I hardly knew anything of his personal life. It became

apparent, quite early, how much Arendt relied on him. He was

thoroughly familiar with the syllabus and reading material,

understood her trains of thought, and especially how her arguments

connected to her books, lectures and other courses. He was

that rare person of many gifts.

Before he became the Trustee of Hannah Arendt's Literary Estate, and concomitant with his many volumes of her own writings, he also helped to review and edit the writings of others. It was originality and critical thought he looked for in a text. I recall a discussion we had of Roberto Callaso’s remarkable book on Greek Mythology, ‘The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony’, unique in the light it throws on the relationship of ancient myth to philosophy, which Jerry had been asked to review for a publisher. I recall discussions on Sybille Bedford, friend of both Hannah Arendt and Mary McCarthy, whose novel, ‘A Legacy’ revealed more about Germany prior to the World War I then many histories. We talked about Dorothy Day whose Catholic Worker movement Dwight McDonald wrote about in The New Yorker. Hannah Arendt and Dorothy Day knew and admired one another and Arendt not only donated money but lectured at the Catholic Worker’s settlement house in New York.

But over the decades, we came back again and again to the courses Arendt taught and the lecture notes she left behind. In a series of emails from September 2014 we discussed the New School course at which we first met. It included not just registered students but also auditors who would later become distinguished in their own right such as Michael Denneny, Peter Stern and Jean Yarbrough. Each of us was assigned a political philosopher to discuss. I was assigned Hobbes. In her lecture notes on Hobbes, Arendt starts with the observation that “nothing can be by itself”. Each of us, although solitary, through introspection comes to the realization that others exist. There is fear in this realization. One of the most important aspects of Hobbes epistemology is that men can only know what they fabricate, but they have neither fabricated themselves or others. Thus begins the quest for power after power and the war of all against all. That leads to the fabrication of the Leviathan which protects each person from every other person. But as Jerry noted during our discussions, in being protected from each other, they become solitary again. The Leviathan protects by isolating. That leads to an important question that was asked of Arendt during her class. ‘Isn’t this the condition of the solipsist whose isolation through the Leviathan leads them to the conclusion only they exist‘? To which Arendt replied ‘The solipsist can never explain to themselves why they are so entirely solitary, and yet not alone’. It is hard to imagine a better definition of modern loneliness? What makes loneliness so unbearable is the knowledge that we are not alone. Loneliness, in the absence of others, is that knowledge.

Or take Arendt’s notes on Rousseau and The French Revolution, distilled from the far more detailed treatment of these subjects in her books. Jerry believed what make the notes from her classes so fascinating is the process of compression that enabled her to not just express core arguments in as few words as possible, but to find connections to other thoughts, in a free flow of ideas, more in the style of her thinking diaries rather than her published books. The idea that “the people” are sovereign, a core belief of the French revolutionaries and now being made popular by Elon Musk, was not, as she points out, a belief held by the founders of the American Republic. It is the Constitution that was sovereign, not the people. The Constitutional Republic they created was a rare example of political thinking and acting that was outside the great tradition. They did not want majority rule and were terrified of its consequences. As John Adams famously put it, “Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide”.

There were the discussions we had concerning Arendt’s writings on Karl Marx from the Christian Gauss Lectures she delivered at Princeton University (1953), writings that Jerry was the first to publish selections from and that were later curated and analyzed thoroughly by ‘Hannah Arendt’s Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Arendt had begun the journey that ended in the Gauss Lectures after she finished the American Edition of the ‘Origins of Totalitarianism’ with a series of grant applications, intending to find the point at which the great political tradition, begun by the Greeks and continuing into modern times, had broken. The journey ended, decades later with the realization that there was no such breaking point. It had been broken all along. The belief that politics was the study of ‘ruling and being ruled’, inherited from prehistoric times, ended up getting passed from generation to generation, each adding its own metaphysical justifications, yet repeating over and over like lunar cycles. Arendt concluded Marx, far from being a break in that tradition, (what many of the institutions during this cold war time wanted as a conclusion) was in fact its end. Neither he, nor anyone before him could jump over the great traditions shadow.

To break out of the cycle one had to get off the staircase of traditional political thought, and think in a new way. So Hannah Arendt developed what she described as “die Hintertreppen” (the back-staircase method, Denktagebuch, Heft III, 22, pp. 69 top of page) where one thinks politically from minority or discarded viewpoints (what she called, in another context, the “hidden gems”). It enabled her to discover a novel form of government based on ideology and terror, the banality of evil, and a new politics of human plurality. It also explained why “no path could be paved from the great tradition ("warum aus der großen Tradition keine Wege gebahnt werden konnten”, ibid).

As I write these words, the new President and his underlings (with apparently much approval) has taken a wrecking ball to our federal government and to its Constitution (what the historian Timothy Snyder has called an attempted coup d'état). Nobody rings a bell on the day the dictatorship arrives. In an email not long before the last election, Jerry and I talked about the Hannah Arendt both of us knew especially in those last years. It was not the Arendt many people write about today. After Nixon’s impeachment there was much celebrating and great hopes for the coming 1976 Bi-Centennial. But Arendt was not celebrating. With the cold war, Vietnam, and Nixon’s political crimes, something had irreparably broken. Her despair was barely palpable. In a letter written by J. Glenn Gray dated April 9, 1975 he urges her not to be so angry and to cheer up. In another, he admonishes her for expressing such despondency. Everyone was celebrating Nixon’s pardon, but Arendt understood that pardoning crimes without punishment is only an invitation to more crimes.

Later, replying to a request to speak at an upcoming Bi-Centennial event, Arendt declines describing the United States as a country of which she has occasionally been fond. She then adds ‘since I have been told to cheer up, I will just claim old age’.

Politics, is not a social science or artificial intelligence experiment that can be run backwards if things don’t work out. We are all left with the consequences. What I believe Hannah Arendt saw, in those last years, was a first glimmer into a return of the neo-liberalism of her youth, that is to say, a return to the world she had been born into and then catapulted out of. But that it might happen so slowly people would not perceive what had changed. After all, did she not say only after Totalitarianism had passed would the true character of the age reveal itself? Thus had she lived another decade of more, she might have written quite different books? For by the early 80s that glimmer, first visible in her last years, emerged into full light of day.

Just after Donald Trump started the first flights of refugees to detention facilities at Guantanamo, he reissued an executive order for a new National Park containing statues of American Heroes, something originally started towards the end of his first presidential term. Mentioned in a speech on July 4, 2020 the original executive order was dated July 8, 2020. It does not give any names. Later, a list was published containing the names of several dozen people. Just before he vacated the Presidency (in January 2021), more names were added; among them, as was widely reported, the name of Hannah Arendt.

Biden extinguished the original 2020 order but upon assuming the presidency again Trump reissued it. And there, apparently, Hannah Arendt will sit among assorted Hollywood stars, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Amelia Earhart, Elvis Presley, Johnny Appleseed, Shirley Temple, and many more. Karl Marx said that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce. In his last email, only days before the election, Jerry reminded me that laughter is always the best weapon to use against tyrants.

One of his favorite poems was written by the great Viennese satirist and essayist Karl Kraus. Like no other, Kraus had foreseen the disaster into which Europe was headed prior to World War I, and like no other, he wrote about it with enormous humor, clarity and compassion. Faced with the catastrophe that was the Third Reich, Kraus (who died in 1936) wrote this poem. With the passing of Jerome Kohn, we are truly on our own, together.

Man frage nicht Ich bleibe stumm

Man

frage nicht, was all die Zeit ich machte.

Ich bleibe stumm;

und

sage nicht, warum.

Und Stille gibt es, da die Erde krachte.

Kein

Wort, das traf;

man spricht nur aus dem Schlaf.

Und träumt

von einer Sonne, welche lachte.

Es geht vorbei;

nachher war’s

einerlei.

Das Wort entschlief, als jene Welt erwachte.

Don’t ask me why I haven't spoke

Don’t

ask me why I haven't spoke.

Wordless

am I,

and

won’t say why.

There

is only silence because the earth broke.

No

word redeems;

only

speeches in dreams.

Of

a sun that laughs at the sleeping dreamer.

The

world waxes and wanes;

the

difference is none.

The

word died when the world awoke.

Die Fackel, July 1934

Celso Lafer, São Paulo

I first met Jerome Kohn – Jerry – in 1970 in New York. He was then Hannah Arendt’s research assistant at the New School for Social Research and he ushered me to her office, to talk with her after having had the privilege of being her graduate student at Cornell University in 1965. In my visit to Hannah Arendt we discussed plans for the publication of her books in Brazil. That started in 1972 with the Brazilian edition of Between Past and Future that she followed with interest with the caveat that the only previous contact she had with the Portuguese language was skimming newspapers in Lisbon on her way to the United States.

1970 was so the point of departure for my long standing intellectual relationship and friendship with Jerry, that lasted until his passing away in November of last year – his inter homines esse desinere in Arendt’s formulation. Not living in the US, I did not have the opportunity of seeing and being with him continuously, yet I did meet him off and on when I was in New York. We exchanged ideas and reminiscences of Arendt’s life and work, their pertinence for the understanding of our worldly circumstances, followed by many e-mails throughout the years.

I shared with Jerry the privilege of having been a student of Hannah Arendt and we both (together with Elizabeth Young-Bruehl) opened our minds to the “winds of thought” attending her course on “Political Experiences in the 20th Century”, given at Cornell in 1965 and at the New School in 1968. This was the common inspiring bond of our devotion to the legacy of Hannah Arendt.

Jerry was close to Hannah Arendt, her person, forma mentis and way of being. He organized with curatorial care her papers for the Library of Congress to the benefit of all Arendtians and nobody was more knowledgeable of what they reveal and illuminate of her trajectory. He shared his knowledge and erudition with amicable generosity with all those that were interested and concerned with Hannah Arendt’s life and work.

When we were her students, Hannah Arendt was a well known, but somewhat controversial academic personality. She had not yet reached the status of a recognized and outstanding thinker of the 20th century. She became, in my view, a classic in the sense of Italo Calvino - she never stops saying what she has to say. Jerry concurred in transforming Hannah Arendt into a classic by enlarging the corpus of the fermenta cognitionis of her work.

Jerry excelled in this task as the curator of Hannah Arendt’s literary trust. The wide-reaching expansion of the corpus of her work was a result of the many volumes he edited, organizing her uncollected and unpublished texts. His endeavors were presented with admirable introductions that were also a labor of scholarly love and friendship, discernment and erudition. This was an initium that started with the publication of Arendt’s “Essays in understanding – 1930-1954”; followed in 2003 by the texts of “Responsibility and Judgment”; in 2005 by the mosaic of “The Promise of Politics”, subsequently by “The Jewish Writings” in collaboration with Ron Feldman in 2007, and “Thinking Without a Banister” in 2008.

All these volumes amplify the understanding of the threads of her thought, the scope of her concepts and categories and the traits of her admirable and fascinating personality.

When Jerry received the Hannah Arendt Prize in Bremen, I wrote to him in December, 17, 2019, saying to him that “no better name than yours is entitled to this distinction. It is a most deserved recognition of the multiple dimensions of your continuous devotion to the life and legacy of Hannah Arendt. It is an act of justice and corresponds to the Roman principle of the suum cuique tribuere.”

Martine Leibovici, Paris

In memory of Etienne Tassin (1955-2018)

The first time Etienne Tassin and I met Jerome Kohn was at the international conference in Clermont-Ferrand devoted to the work of Hannah Arendt, on April 6 and 7, 1995. It was organized by Etienne Tassin and Anne-Marie Roviello1. Wolfgang Heuer was there, and Jerome spoke on “Evil and plurality: Hannah Arendt’s path to The Life of the Mind”2. I translated the text and responded to Jerome’s talk. In the book that came out of this colloquium, Etienne recalled how the dialogue that took place in Clermont-Ferrand was not

between ‘professional thinkers’ [...] but between ‘friends’. Everyone present will certainly remember these days for their warm, friendly atmosphere, as if, far from academic polemics and rhetorical battles, it had been a question of nothing other than thinking in common3.

On the one hand, all of us who came to Arendt’s work in the 1980s were impressed by Jerome, who had been very close to the author we were so interested in, and for us he was like a living link to her. On the other hand, he was the last to introduce himself as a “professional thinker” and he was perfectly at home in the atmosphere that Etienne describes, and we experienced this same atmosphere whenever we met him again.

Little by little, under the impetus of Etienne, that great maker of philosophical friendship all over the world, a network of philosophers inspired by Arendt's thought was formed in Europe, with among others Wolfgang Heuer and Antonia Grunenberg and in Latin America Claudia Hilb. At the time, Antonia had initiated a meeting of German, Italian and French researchers, entitled Renewing political thinking after Hannah Arendt. It took place from June 7 to 11, 2005, at the Villa Vigoni, a German-Italian research center on the shores of Lake Como. Three intense days, like a utopian bubble where all material needs were taken care of in a truly luxurious way, in a place of striking refinement and beauty, that gave us the privilege of devoting ourselves from morning to night to collective reflection on Arendt’s political thought. Jerome was there as a special guest, and he would intervene as he pleased in the discussions. The luxury of this setting didn’t make us forget the spirit we - well, most of us - loved in Arendt, as one evening after dinner we started singing a whole European repertoire of revolutionary songs. Jerome was ecstatic.

The following year, from November 16 to 18, 2006, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Arendt’s birth, four of us - Anne Kupiec, Géraldine Muhlmann, Etienne Tassin and myself - organized an international conference at Paris Diderot University, Crises de l’Etat-Nation. Pensées alternatives. The highlight of the conference was when Géraldine Muhlmann asked Elisabeth Young-Bruehl and Jerome to talk about their personal relationship with Arendt, and more specifically about her last years. Then, again moderated by Géraldine Muhlmann, we experienced a fascinating exchange between Elisabeth and Jerome. This concerned both the Arendtian critique of the concept of sovereignty, which they used to analyze what was new at an international level in those years, with an emphasis on the way the USA was implementing security (the suspension of habeas corpus at Guantanamo, the militarization of the world, etc.), but also on the new form of “religiously inspired terrorism”. Their exchange considered also the possibility or otherwise of an alternative to sovereignty4. Etienne and I had also been asked by the Centre Pompidou to take part in this anniversary event. So, taking advantage of Jerome’s presence in Paris, he also spoke at the conference Hannah Arendt au présent. La politique a-t-elle encore un sens? (November 24-25, 2006)5

After that, Jerome was always immediately available whenever I needed advice or information. I always felt his friendly warmth in the “Dear Martine” with which he would start to begin his e-mails. And it was only natural that Aurore Mréjen and I should ask him to contribute to the volume of the Cahiers de L’Herne devoted to Arendt, which we edited in 20216. From the text we published, in which Jerome’s intense sensitivity to poetry is apparent, I’d like to offer this passage in which he vividly recalls Hannah Arendt, the teacher he knew:

Nothing pleased Arendt more than the appearance of a student in a seminar determined to express his or her thoughts on a topic under discussion. If the student stumbled a little at first, which was usual, and then apologized for their jitters, Arendt rather abruptly said, “Never mind how you are – appear as you would like to be – make the world a little better.” Then the well-lit room in which the seminar was held seemed to change, almost like an optical illusion. For to have a sense of oneself as you might be – and not as you are – is akin to becoming a spark, a tiny source of light. Metaphorically, it is a ship’s light beckoning in the dark and being recognized by other ships, in a sea that has no safe harbors. In Arendt’s seminar, it was an immediate experience of illumination, of emerging from the dark7.

Jerome Kohn was one of these students, and he has been faithful all his life to the event of his encounter, work and friendship with Arendt. For those who have been around him at one time or another, the world has been made a little better. With the sandstorm beginning to blow in from the desert the world is becoming, we all need oases, to be able to endure and withstand the sandstorm. May the memory of moments spent with Jerome sustain us.

At the Villa Vigoni. From

left to right : Gerôme Truc, Antonia Grunenberg, Marc Le Ny,

Valérie Gérard, Martine Leibovici, Jean-Claude Poizat,

Jerome Kohn.

Etienne laying in the garden of the Villa Vigoni

Volker März, Berlin

Das Foto entstand 2006 bei der Veranstaltung zu Arendts 100. Geburtstag in der Niedersächsischen Landesvertretung in Berlin.

Adriano Correia, Goiânia

I first had the opportunity to get to know Jerome Kohn's work as soon as I came into contact with Hannah Arendt’s work, back in the 1990s. From the beginning of my studies of Arendt’s work, I associated the knowledge of her thought with the zeal with which her former assistant treated her papers. From the publication of works such as Essays in Understanding - 1930-1954, in the mid-1990s, and then with the appearance of works such as The Promise of Politics, and Responsibility and Judgment, I understood very well the importance of Jerome Kohn’s diligence for the qualitative reception of Arendt’s work. Also in the mid-1990s, I was able to read the beautiful text “Evil and plurality: Hannah Arendt's way to The life of the mind, I”, contained in Hannah Arendt: twenty years later, organized by Kohn and Larry May. This was the first of a number of texts by him to be translated into Portuguese, many of them as introductions to books by Arendt that were organized posthumously.

The growing dissemination of Jerome Kohn's texts among us has coincided with a rise in interest in Hannah Arendt's work in the Brazilian university scene, which has also been mobilized by these posthumous editions of her texts organized by Kohn and by the publication of increasingly accurate translations. In addition, with the emergence of numerous authoritative works discussing Arendt's thought, Kohn has become widely read and cited among us. When I was a visiting professor at The New School, he had already retired, but I still had contact with him through Richard Bernstein, who also left us recently. Jerome Kohn took part in some online activities in Brazil even after his retirement.

The carefulness with which Jerome Kohn treated Arendt's work, both in terms of its dissemination and its interpretation, is evocative of Arendt's own care with the edition of Walter Benjamin's works, which occupied her for a long time. In the disputes surrounding the publication of her friend's work, Arendt insisted on her duty of loyalty to departed friends. Jerome Kohn contributed with his loyalty to the growing vitality of Arendt's work. His own interpretation of her work will remain with us as a permanent inspiration for reflection and understanding of our dark times. Like her, he will remain.

Helgard Mahrdt, Oslo

Meine erste Begegnung mit Jerome Kohn war 2002, und sie war eine virtuelle Begegnung. Zu dem Zeitpunkt war ich mit einem Stipendium des John W. Kluge Centers an der Library of Congress, um über Hannah Arendts erste zehn Jahre in Amerika zu forschen, also von 1941, als sie in New York ankam, bis 1951, als ihr Buch The Origins of Totalitarianism erschien. Ich stieß auf Arendts Briefe an Alfred Kazin, und fand in der New York Public Library im damals noch nicht katalogisierten Nachlass Kazins Briefe an Hannah Arendt. Knut Olav Amas, der damalige Redakteur der norwegischen Zeitschrift Samtiden begeisterte die kleine Auswahl von Briefen, die ich ihm mailte; und so wandte ich mich an Jerome Kohn, Hannah Arendts Nachlassverwalter, mit der Bitte, den Briefwechsel in Samtiden veröffentlichen zu dürfen. Dieses zufällige Forscherglück war der Anfang meiner Freundschaft mit Jerry.

Begegnet bin ich ihm seitdem mehrfach, zum ersten Mal im Mai 2005 im Literarischen Colloquium in Berlin, auf der von Prof. Irmela von der Lühe und Wolfgang Heuer organisierten Tagung „Dichterisch Denken: Hannah Arendt und die Künste“, dann im Jahr darauf, auf der Tagung in Paris „Crises de l’Etat-nation. Pensées alternatives“. Dort wählten Elisabeth Young-Bruehl und Jerome die Form des Gesprächs, um miteinander über Hannah Arendts Begriff der Souveränität nachzudenken. Hannah Arendt verstand das Gespräch zwischen Freunden als einen Ort, an dem diese zur Erscheinung bringen, wie sich ihnen die Welt von dem ihnen je eigenen Stand aus darstellt. Im Gespräch miteinander erschließen wir uns die „Gemeinsamkeit der Welt“ und zeigen, wer wir sind.

Das Risiko, in Erscheinung zu treten, auf die „ursprüngliche Fremdheit“ zu verzichten, bedeutet, schreibt Hannah Arendt in ihrem Essay „Gedanken zu Lessing“, dass wir bereit sind, uns im Miteinander unter unseresgleichen zu bewegen. Auf der Tagung in Berlin sprachen Jerry und ich zum ersten Mal über Arendts Essayband Menschen in finsteren Zeiten. 1968 schrieb Publisher's Weekly über den Essayband, er habe “a deep-running theme of passionate caring for humanity, friendship and a commitment to the world”. Jerry und ich waren uns einig, dass „Gedanken zu Lessing“ zu den von uns bevorzugten Essays gehörte. Gemeinsam mit Fred Dewey und Wolfgang Heuer veranstaltete ich im Frühjahr 2014 ein zweitägiges „Hannah Arendt Reading Seminar“, in dem wir diesen einen Text „Gedanken zu Lessing“ diskutierten; Jerry schrieb mir: “It all looks wonderful! I only wish I could sign up for the seminar. I‘ve known Wolfgang as long as I’ve known you, and more recently Fred Dewey has become close friend.”

Begegnet bin ich ihm seitdem mehrfach, zum ersten Mal im Mai 2005 im Literarischen Colloquium in Berlin, auf der von Prof. Irmela von der Lühe und Wolfgang Heuer organisierten Tagung „Dichterisch Denken: Hannah Arendt und die Künste“, dann im Jahr darauf, auf der Tagung in Paris „Crises de l’Etat-nation. Pensées alternatives“. Dort wählten Elisabeth Young-Bruehl und Jerome die Form des Gesprächs, um miteinander über Hannah Arendts Begriff der Souveränität nachzudenken. Hannah Arendt verstand das Gespräch zwischen Freunden als einen Ort, an dem diese zur Erscheinung bringen, wie sich ihnen die Welt von dem ihnen je eigenen Stand aus darstellt. Im Gespräch miteinander erschließen wir uns die „Gemeinsamkeit der Welt“ und zeigen, wer wir sind.

Das Risiko, in Erscheinung zu treten, auf die „ursprüngliche Fremdheit“ zu verzichten, bedeutet, schreibt Hannah Arendt in ihrem Essay „Gedanken zu Lessing“, dass wir bereit sind, uns im Miteinander unter unseresgleichen zu bewegen. Auf der Tagung in Berlin sprachen Jerry und ich zum ersten Mal über Arendts Essayband Menschen in finsteren Zeiten. 1968 schrieb Publisher's Weekly über den Essayband, er habe “a deep-running theme of passionate caring for humanity, friendship and a commitment to the world”. Jerry und ich waren uns einig, dass „Gedanken zu Lessing“ zu den von uns bevorzugten Essays gehörte. Gemeinsam mit Fred Dewey und Wolfgang Heuer veranstaltete ich im Frühjahr 2014 ein zweitägiges „Hannah Arendt Reading Seminar“, in dem wir diesen einen Text „Gedanken zu Lessing“ diskutierten; Jerry schrieb mir: “It all looks wonderful! I only wish I could sign up for the seminar. I've known Wolfgang as long as I've known you, and more recently Fred Dewy has become close friend.”

Die Gespräche der Freunde gelten „der gemeinsamen Welt“, darin manifestiert sich ihre politische Bedeutung. Als ich Jerry im Dezember 2017 fragte, was das Jahr 2018 Europa und der Welt bringen würde, ob Donald Trump die amerikanische Botschaft nach Jerusalem umsiedeln würde, antwortete er: “I hope 2018 will be a better one than 2017. I am glad the UN censured Trump so emphatically for his attempt to move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. He is a real vulgarian, very stupid, and thoroughly dishonest.” Das Besondere an den Gesprächen zwischen Freunden ist, dass sie von der Freude darüber, dass es den Freund gibt, durchdrungen sind. Mit Jerry konnte ich Dinge wie die Auswahl von Arendt-Büchern, die ins Norwegische übersetzt werden sollten, besprechen, Jerry freute sich mit mir über gelungene Projekte wie die norwegische Neuübersetzung von Arendts Essay „Macht und Gewalt“. Zwischen uns war nicht nur die gemeinsame Welt das Thema, sondern es gab auch Platz für die menschliche Beziehung, für die Befindlichkeiten. Als ich ihm einmal schrieb, dass ich an mir zweifelte, antwortete er, “Remember what Spinoza said: ‚Everything worth doing is difficult‘“.

Arendt glaubt an die „Aufschluss gebende Qualität“ der Worte. Damit uns die Alltagswelt verständlich bleibt, brauchen wir den öffentlichen Bereich, der „Licht auf die menschlichen Angelegenheiten“ wirft. Wir brauchen aber auch Worte, „mit denen wir leben können“. Deshalb müssen wir auch die Frage stellen, in welchen Begriffen wir denken. Damals, im Mai 2005, als ich Jerry zum ersten Mal in Berlin begegnete, sprach ich über Hannah Arendts Benjamin-Essay, und über die Metapher, die für Benjamin „das größte und geheimnisvollste Geschenk der Sprache” war. Als im Januar 2021 der Angriff auf das Capitol in Washington einen Schock auslöste, las ich unter den Versuchen, die Ereignisse zu verstehen, auch den Marxschen Begriff vom „Lumpenproletariat“. Aber war dieser Begriff wirklich einer, der die Wirklichkeit aufschließt? Ich schrieb an Jerry, “I wonder whether this notion is backward, and taken out of its own time may not be helpful for understanding these groups of today. What, then, might be a proper word? This seems to me important, also in reference to a note in the Denktagebuch: "Wofür die Sprache kein Wort hat, fällt aus dem Denken heraus". To me it seems as if this statement can be linked to the passage in On Revolution: ... to understand an event conceptually”. Jerry antwortete,

I agree with you that the Marx's "Lumpenproletariat" does not suit the hoodlums that broke into the Capitol in Washington in January. They are not the product of the bourgeois economy, but simply a-social Dummköpfe.

You mention experience especially in regard to language. that is most important, and as far as I know, has not yet been fully probed. As you say Arendt says, experience vanishes if it is not captured in words, at least how I understand "Wofür die Sprache kein Wort hat, fällt aus dem Denken heraus." The question is what sort of words? To me this suggests what I call, perhaps misleadingly, Arendt's poetic thinking. Of course, that is her term, used with regard to Benjamin, but it seems to me at least as well suited for her. Doesn't the metaphor take the place of the concept in Arendt? I think for her "understanding conceptually" does not mean using handed down concepts but rather seeing conceptually, that is, grasping experience, through metaphors. Traditional concepts are too stable for her. The world of experience, which concerns her, is anything but stable. Contingency negates stability, and thereby let's freedom be. Die Freiheit frei zu sein. That refers to the conditions that must be met to participate in the activity of being free, whether in action or in thinking. These are all such huge matters, and require an essay or book -- or essays and books -- to begin to understand. But this one I can say, experience depends on language, and language depends on thinking, and thinking is only possible when one is sufficiently withdrawn but NOT fundamentally separated from the world.

Jerry weilt nicht länger „unter Menschen “ („inter homines esse“); ein Freund ist aus meinem Leben verschwunden und hinterlässt eine Lücke. Aber er hinterlässt auch seine Aufsätze, die von ihm edierten Sammlungen von Arendt-Essays, zusammen mit den profunden Einleitungen, die er geschrieben hat; und dazu neue Fragen und Aufgaben.

Wout Cornelissen, The Hague

I first met Jerry Kohn in 2013, when I was introduced to him by Thomas Wild. I had just started a postdoctoral fellowship at Bard College, and Thomas Wild had asked me to become one of the editors of the new, critical edition of The Life of the Mind. The first few times, Jerry and I met as part of a larger group. Not much later, once I had begun doing the archival research on The Life of the Mind, I had the chance to meet with Jerry individually.

Jerry’s mind was extraordinarily alive. It was hard not to feel his words, both in conversation and in correspondence. Usually, he invited me for lunch in a bistro in Manhattan, not far from his apartment, after which we walked on the sidewalks together, crossing avenues and streets, on our way to our respective next destinations. When we spoke, Jerry would always ask for my opinion, when a certain book by someone on Arendt had just come out, or when someone had said something about a certain matter. He would never just “opinionate”: he was always interested in what you would think of the matter—thus living out Arendt’s insight that meaning isn’t coercive and that judgment depends on the willingness to place yourself in the standpoints of others. Gradually, we also started corresponding via email. Almost without exception, Jerry would reply within 24 hours, which would lead to a string of messages between us around a certain topic. Once the thread became too long, he would start a new one.

The Life of the Mind was very dear to him, not only because of its substance—he believed the book was “years ahead of its time”—but also because he had been there from the moment Arendt had begun working on it, after she arrived at the New School, where he served as her teaching assistant until her death in 1975. When he gave “pro-seminars” to her lecture course on “Thinking” and “Willing,” she shared a photocopy of each chapter, which he had kept. He generously lent these to me so I could compare them—I remember sitting on a Long Island Railroad commuter train with a box of typescripts, guarding it with my life.

After Arendt’s death, he had assisted Mary McCarthy in tracing Arendt’s references and answering other questions when she was editing Arendt’s text for publication. When he read an essay I had written on Arendt’s metaphors of thinking, he agreed with its substance but added: “you should find yourself a Mary McCarthy!” Around that time, he was working on Thinking Without a Banister, the last of the five volumes of Arendt’s published and unpublished essays he edited. When it came out, he generously gave me a copy, and added that he would now have to “sleep like a bear.”

During the Covid-years—Jerry spoke of “the plague”—we couldn’t meet in person, but our correspondence continued, now with longer interludes. Sometimes, when I bothered him again with a question about certain materials or facts, he grew impatient with me. I had to play the role of the philologist, mapping materials, meticulously reconstructing the genesis of The Life of the Mind. Jerry sometimes mistook this for a lack of interest in content, eager as he was to engage in, and continue, a dialogue about the matters, rather than the materials, of thinking. Yet, we had a shared goal: to let Arendt’s own words speak to their readers, in order to allow for a better understanding of her work and its meaning in the world we live in.

The volumes of our edition of The Life of the Mind came out in April 2024. Upon receiving the news from us, Jerry sent his congratulations and shared his exhilaration. In May, my partner Mirjam and I visited Jerry and his partner Jerry in Cutchogue. It was the first time I saw Jerry in person again in more than three years, and the first time we met each other’s partners. It was a most joyful day, filled with lively conversation and lots of good laughs. When I handed the volumes to him, Jerry replied that he would first need to “strengthen my arms to lift them”! I was excited, but also a bit apprehensive: what would Jerry think? A few weeks later, I received an email message from him:

“This only a quick note to say that I have read the first volume of your work. It is like rummaging through a treasure chest! I have a million questions, but now have time only to say how wonderfully enjoyable it is to read The Life of the Mind in your edition, and also, and just as much, the array of Hannah’s writing you have gathered to supplement it. It is delightful to realize that what is between these blue covers is there to bathe in every day.”

When the sad news of Jerry’s passing came, I realized how fortunate we had been to see him in May. Compared to many of the “gatekeepers” of the Nachlass of other thinkers, Jerry was exceptionally generous. He made it his life’s work to let as many people as possible, all over the world, read Arendt’s work. He once wrote to me: “The urgency I find as her literary trustee is to keep her works available for those who, possibly, may be willing to care for at least parts of what is now ceasing to be a common world.” To this end, it was important to him readers understood not only Arendt’s words, but also who she was as a person: “Hannah knew no fear.”

1Anne-Marie Roviello (1948-2018) was one of Arendt's best interpreters in those years. I dedicate also this text to her memory.

2« Le mal et la pluralité. La voie d’Arendt vers La vie de l’esprit », in Hannah Arendt. L’humaine condition politique, dir. Etienne Tassin, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2001.

3Ibid., p. 7-8.

4The proceedings of this conference – Hannah Arendt. Crises de l’Etat-nation , dir. A. Kupiec, M. Leibovici, G. Muhlmann, E. Tassin - were published in Paris, Sens&Tonka, 2007. Some of these texts have been translated in Social Research, New York. Hannah Arendt's Centenary: Political and Philosophic [Part II] Vol. 74 No. 4 (Winter 2007).

5For Jerome's contribution to this event, listen to: https://replay-cdn.bpi.fr/fr/doc/2112/Hannah+Arendt_+penser+entre+le+passe+et+le+futur

6In 2013, Aurore included a telephone interview with Jerome in her radio documentary Hannah Arendt et le procès d'Eichmann. La controverse, broadcast on France Culture on May 7, 2013.

7«Les manifestations de l’étrangéité», in Arendt, Cahiers de L’Herne, dir. M. Leibovici et A. Mréjen, 2021, p. 299.

![]()